|

|

The Neuron Dance

by Sandi

& Dan Finch

No, that’s not new choreography. It is a “dance” we do, though, every

time we take a workshop or watch a video. The “neuron dance” is a term

that has come to describe how the brain learns something new,

encountered of all places in a book on how to play bass.

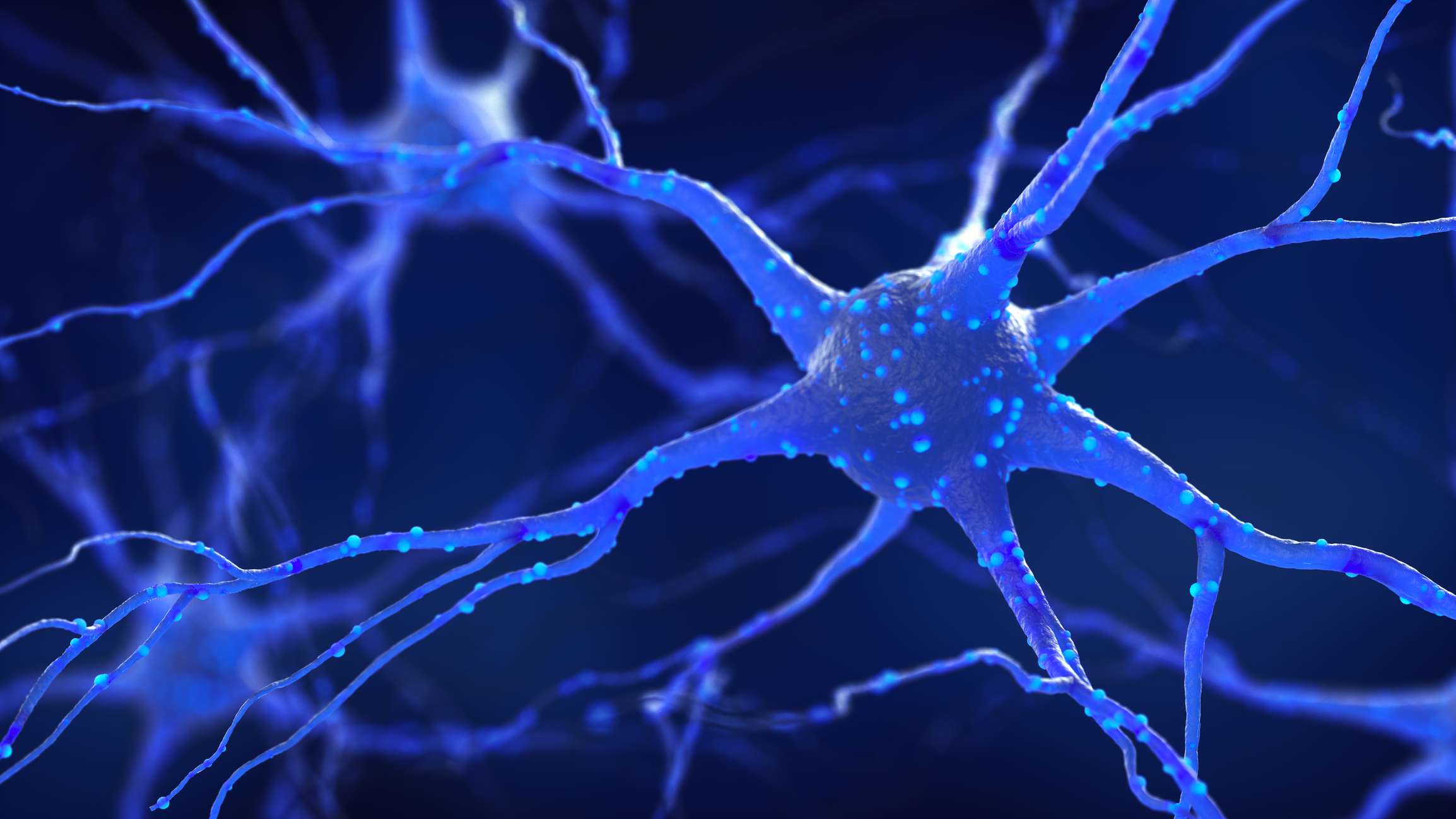

Much like the chips in a computer, billions of cells called neurons

exist in the brain to transmit information along circuits called

synapses. When we try to learn something new, the brain first has to do

is work out how that new task is to be done and chart the pathways for

it. As you practice the new task, the neural pathway thickens and the

concept becomes ingrained. Eventually, what you thought of as difficult

becomes easier to you.

Much like the chips in a computer, billions of cells called neurons

exist in the brain to transmit information along circuits called

synapses. When we try to learn something new, the brain first has to do

is work out how that new task is to be done and chart the pathways for

it. As you practice the new task, the neural pathway thickens and the

concept becomes ingrained. Eventually, what you thought of as difficult

becomes easier to you.

The mistake we all make when learning something new is not allowing

enough repetition for that ingraining to happen. We call it developing

“muscle memory,” but it is that big “muscle” in the head that is

learning.

In the old days of round dancing, dancers danced routines without cues.

Minutes in the annals of the Round Dance Teachers Association of

Southern California tell its members in the 1960s to start cueing a

dance but only the first time through and leave the repeated part

uncued. How were the dancers able to do that? Repetition is the most

obvious clue, but it turns out there is a science to learning.

How We Learn: The Simple Truth About When, Where & Why It Happens,

by New York Times science writer Benedict Carey, showed up on my Kindle

reading list about the same time someone asked why we seem to have

forgotten so much during the pandemic. In the book, he calls the brain

“an eccentric learning machine” because we can’t control how it learns

or how those neurons receive signals, fire, and pass them along down

the pathway. They just do. And if they aren’t used, they don’t.

Science tells us there are ways to help the brain do its dance. In

general, the brain picks up patterns more efficiently when given a

mixed bag of related tasks, according to a book called The Dancer’s

Study Guide. This means tackling a new idea in several ways.

- First, take notes. Writing helps ingrain what you are

hearing, making

use of two of your senses at one time. Then, repeat the information to

yourself, calling on another sense. Relate what you are learning to

something you already know.

- Go through it all again in 24 hours. This is the science

behind why

those Sunday reviews at festivals so miraculously bring the Saturday

teaches into focus.

- Take a five-minute break each hour. If you’ve been to a

festival or

workshop, you know the instructor will break after an hour. This gives

your brain a rest, and a clearer mind means it is easier to pick up

information. [www.entrepreneur.com]

- One of the most important ideas is to tell yourself you CAN

do it.

This last one is nothing new. Back in the 1980s, Eddie Palmquist told

the members of his exhibition team the same thing. To be able to dance

an uncued formation routine, he wrote, “you must make up your mind you

are going to learn it. Alert your subconscious.” He had some other

ideas for the Palmquist Dancers that he fortunately put in writing.

- Try to visualize the main figure in each section of a

routine, he

wrote. That will trigger your brain to bring the whole section to mind.

- Study the head cues of a dance between dance sessions. “It

is necessary

to do a little homework,” he wrote. While dancing the routine, mentally

tie it in with the music.

- Know the fundamentals of each figure and understand its

alignment in general and in a particular routine.

- Most importantly, he added, “repetition is necessary.” The

trick here

is, as the old saying goes, “practice makes perfect but only if the

practice is perfect.” If you continually do the figure or routine

wrong, the synapses are building a path to always doing it wrong.

This “neuron dance” has been the subject of many studies, in many

creatures. MRIs can show the synapses at work, “lighting up" as

thoughts occur. One study determined that bees searching for a new hive

describe the options to fellow bees with an actual “dance.” Lots of

neural pathways light up in the brains of monkeys when they have a

choice to make.

MRIs have shown that when a dancer watches a dance video, areas of the

brain associated with action “light up” even though the person watching

is not moving. This is thought to occur because action neurons are

connecting just on seeing a familiar pattern. [Science Daily, 2017]

You can learn a routine from a video, called observational learning.

But MRIs have shown that participants who learned solely by video had

less brain activity [learned the new motor skill less rapidly and

less precisely] than dancers who learned through practice with a coach.

[9 Linectics, 1999]

One interesting study showed that training children in music improved

their IQ scores, even for math and linguistics. [Dana Foundation,

Cerebrum, 2021] Maybe that explains why doing a new dance step to music

helps to learn it, but don’t bank on being better at solving math

problems after your next dance lesson :-)

From a club

newsletter, March 2022,

and

reprinted

in the Dixie Round Dance Council (DRDC)

Newsletter, April 2022. Find a DRDC Finch archive here.

|